Science gains meaning when it is shared. And irrespective of the audience, whether a classroom full of students, a clinic full of doctors, or citizens of a community, or the whole wide world, science communication offers us a chance to learn to tell our story better.

Science often begins in quiet spaces like labs, notebooks, and data files but its true impact is felt only when it reaches people, who directly or indirectly fund science. During my years of research in India, I learned early on that generating knowledge was only half the responsibility of any scientist. The other half was learning how to communicate it to the public: clearly, honestly, and accessibly, to audiences far beyond the scientific community.

I am Vigneshwar, and this blog post reflects on my journey in science communication in India; from engaging students and clinicians to working with public health stakeholders and how these experiences continue to shape my perspective as a researcher at Umeå University.

Doing science in a diverse ecosystem

India’s scientific ecosystem is vast and diverse, spanning cutting edge genomics labs, hospitals, universities, and community-driven public health initiatives. Working at the intersection of research and clinical genomics, I was often positioned between different worlds: researchers, clinicians, students, and policymakers.

Each group spoke a different “language” of science. Communicating effectively meant adapting the same core idea for e.g., a genetic variant, a sequencing workflow, or a research finding into forms that made sense to each audience without losing the essence and integrity.

Communicating with students: Making genomics approachable with visual storytelling

A central part of my science communication work involved mentoring students in research settings and engaging with visiting students during institutional open days at CSIR-Institute of Genomics & Integrative Biology, CSIR- IGIB. During these events, my primary responsibility was to guide students through the sequencing facility and other associated laboratories. I routinely introduced them to sequencing instruments, explained sequencing workflows in accessible terms, and discussed the broader significance of genomics in understanding health and disease.

The open-day activities also included guided visits to the zebrafish facility. Here, I explained the importance of model organisms in disease research, their developmental cycle, and how experimental models help bridge basic biology and clinical understanding. The emphasis was always on adapting explanations to the students’ level of background and interests, and on encouraging curiosity-driven discussion.

In addition to in-person engagement, I also contributed to science communication through digital media. I produced several short videos aimed at increasing awareness about rare diseases. These videos focused on experts explaining disease mechanisms, diagnostic challenges, and the importance of genetic testing in a format accessible to non-specialist audiences, including patients, families, and the common public.

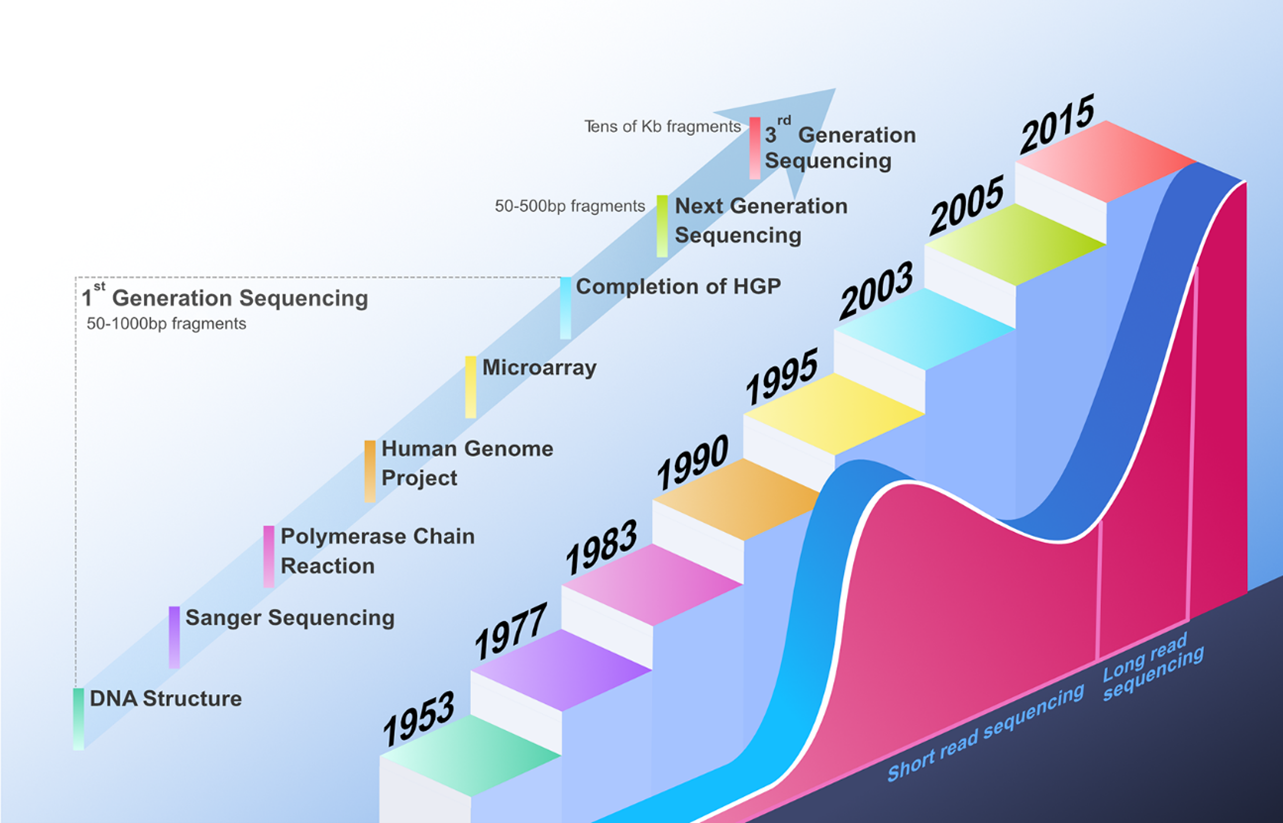

An infographic I did to understand the evolution of sequencing techniques

Bridging research and clinics: Talking across disciplines

A significant part of my work involved collaborating with clinicians, particularly in the context of genetic testing and disease diagnosis. Here, communication had direct consequences. A poorly explained result could lead to misunderstanding; a clearly communicated finding could support better clinical decisions. This required translating genomic data into clinically meaningful insights mainly focusing on relevance, uncertainty, and limitations. Over time, I learned that trust is built not through technical complexity, but through clarity and transparency.

In addition to day-to-day clinical interactions, I also contributed to Continuing Medical Education (CME) sessions for clinicians, aimed at improving their understanding of next-generation sequencing (NGS) data analysis. These sessions focused on practical questions clinicians face: how sequencing data is generated, how variants are filtered and interpreted, and what are the limitations of NGS-based tests.

Rather than turning clinicians into bioinformaticians, the goal was to help them ask better questions of the data, understand confidence and uncertainty in reports, and integrate genomic findings more effectively into clinical decision-making. Designing these sessions reinforced for me that effective science communication often lies in meeting people where they are, respecting their expertise while bridging disciplinary gaps.

CME course on Exome sequence analysis at NIRRCH- Mumbai.

Public health and outreach: Science at scale

Apart from the CME activities, I was also a faculty for the Genetic variant analysis and clinical interpretation program), an intensive three month digital course that enrolled more than 2,000 clinicians, genetic counsellors, and students across over 40 countries. The program focused on training participants in clinical variant interpretation using the ACMG guidelines, with an emphasis on real-world interpretation challenges, case-based discussion, assignments and activities. My role involved contributing to the course content, setting the visual narrative, video production, organizing live streaming events and managing the YouTube channel- GenomicsInIndia and scheduling uploads.

Beyond individual labs and clinics, I also contributed to large-scale genomics and public health initiatives, including population-level studies and pandemic-related sequencing efforts. These projects highlighted the importance of communicating science at scale to administrators, public health officials, and sometimes the common public. In such settings, the challenge was not just explaining what we were doing, but why it mattered. Clear communication helped align expectations, accelerate decision-making, and reinforce public trust in science-driven interventions.

Apart from using non-conventional ways to connect with the broader public audience through social media, I also had the opportunity to work on structured communication for industry. During my time as an industrial postdoc, I designed product brochures, communication mock-ups, and training modules for sales representatives and clients for translating the genomic services/products that we offered into clear, accurate and user-friendly material.

Carrying these lessons forward to Umeå

Looking back, my experiences in science communication in India taught me that communication is not an optional skill for scientists but a core part of responsible research. These lessons now travel with me to Umeå University, where interdisciplinary collaboration and societal engagement are deeply valued.

As I continue to work on my first gig at Umeå – designing a logotype for the genome sequencing initiative for the myocarditis patients, which is my primary research work at Umeå University, I see science communication not as a separate activity, but as something embedded in everyday scientific practice, from how we design experiments to how we share results with the world. Science gains meaning when it is shared.

My current workplace at Umeå University, Sweden.Vigneshwar Senthivel, postdoc in Anne Tuiskunen Bäck lab